From a distance, the collapse of Asia’s great empires appears sudden and dramatic. Within a few decades, political systems that had endured for centuries disintegrated under the pressure of modernity and foreign domination. In contrast, European empires persisted longer, adapting, expanding, and reshaping themselves well into the twentieth century. This difference has often been misinterpreted as evidence of weakness or stagnation in Asia. In reality, the faster collapse of Asian empires reflects structural differences in how power was organized, challenged, and transformed.

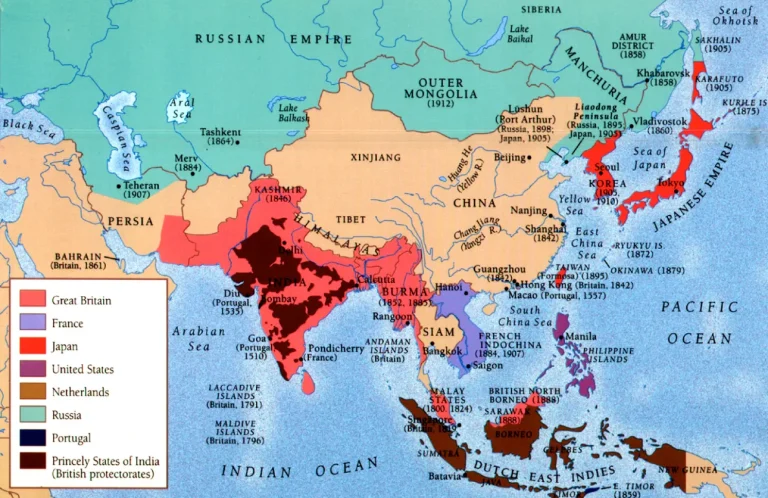

Empire did not mean the same thing in Asia as it did in Europe. Asian empires were often built on moral authority, tribute networks, and flexible sovereignty rather than permanent territorial domination. Their strength lay in stability and continuity, not expansion. When confronted with a world that rewarded speed, extraction, and militarized competition, these systems faced challenges they were not designed to survive.

Source: Colonial-era map of Asia

For centuries, Asian empires governed through layered authority. Power radiated outward from courts rather than being enforced uniformly across territory. Loyalty was negotiated, not imposed. Borders were porous. This model functioned effectively in a pre-industrial world where communication was slow and legitimacy mattered more than control.

European empires operated differently. They evolved through constant warfare among peer rivals. Survival required adaptation. Institutions became centralized. Militaries professionalized. Economies were reorganized around extraction and trade. By the time Europe encountered Asia at scale, it had already transformed itself into a system optimized for domination.

Asia did not fail to modernize. It was confronted with modernity on terms defined elsewhere. European powers arrived with technologies, financial systems, and military doctrines forged through centuries of internal competition. Asian empires faced not gradual change, but sudden shock.

The introduction of modern warfare altered the balance decisively. Industrial weapons, steam-powered navies, and mass logistics overwhelmed traditional defense systems. Empires that had relied on moral authority and negotiated loyalty found themselves vulnerable to force they could not match quickly.

Visual representation of Qing dynasty

In China, the Qing dynasty confronted repeated military defeats that undermined its legitimacy. External pressure combined with internal unrest. Reforms came too late and lacked coherence. Collapse followed not from decay alone, but from compression of crises.

Trade and capital accelerated decline. European empires integrated military conquest with economic extraction. Asian economies were reoriented to serve foreign markets. Revenue drained outward. States lost the ability to fund defense and administration. Sovereignty eroded without formal conquest.

Internal fragmentation magnified external pressure. Ethnic, regional, and class tensions that had been managed through imperial flexibility hardened under stress. Rebellions multiplied. Authority fractured. Empires faced enemies both within and without.

The Qing collapse illustrates this dynamic vividly. Once the world’s largest and most sophisticated empire, it fell within decades of sustained external intrusion and internal revolt. Reform attempts clashed with entrenched structures. Modernization without sovereignty proved destabilizing.

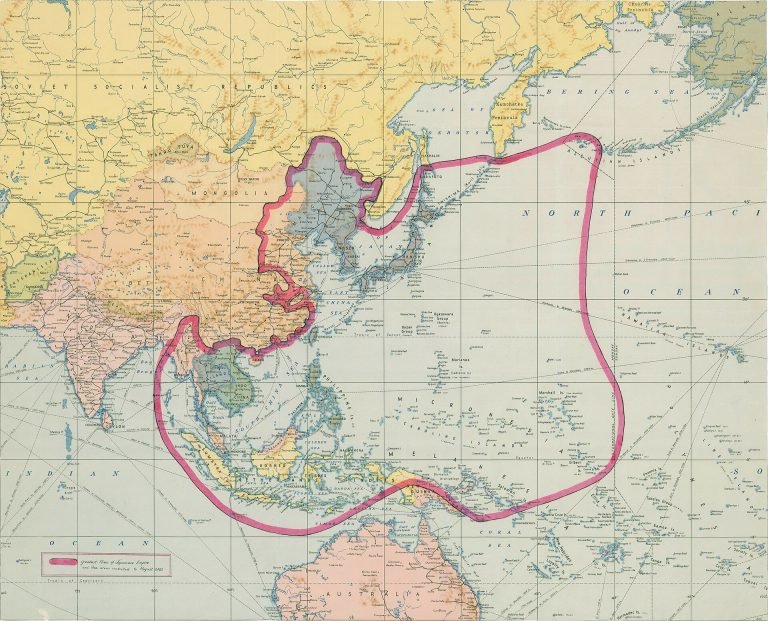

Expansion map of the Japanese Empire

Not all Asian empires collapsed identically. The Ottoman Empire, straddling Europe and Asia, adapted longer by reforming military and administration. Yet even it eventually succumbed to nationalist movements and imperial competition.

Japan offers a unique case. Rather than collapsing immediately, it attempted to become an empire itself. Rapid modernization allowed it to compete temporarily within the European-dominated system. This strategy delayed collapse but ultimately led to catastrophic overreach.

In Japan, modernization was pursued aggressively to preserve sovereignty. Success came at immense cost. Empire building exposed Japan to the same forces that had destroyed others. Defeat ended imperial ambition decisively.

European empires survived longer not because they were morally superior, but because they controlled the rules of the new global order. Asian empires were forced to adapt to systems designed elsewhere. Collapse was accelerated by asymmetry.

Ruins of former Asian imperial centers

Asia’s empires collapsed faster because they faced simultaneous transformation across military, economic, and ideological dimensions. There was no time to adjust gradually. Survival demanded reinvention faster than institutions could manage.

This collapse reshaped Asia permanently. Empires dissolved into nation-states. Borders hardened. Authority shifted from moral legitimacy to coercive sovereignty. Violence accompanied transformation.

Understanding this history challenges simplistic narratives of decline. Asian empires did not fail because they were inferior. They collapsed because the world changed around them at unprecedented speed.

The rapid collapse of Asia’s empires explains much about modern Asia. It clarifies why nationalism emerged so forcefully, why borders remain contested, and why memory of empire remains sensitive.

Empire in Asia ended quickly, but its consequences endure.

Comment (0)